In this “yellow paper”, we discuss Themelio’s abstract model of the state of the blockchain. Themelio uses a richly-scripted coin-based model that is different from both the simple coin-based model of Bitcoin and the accounts-and-contracts model of Ethereum.

Basic concepts

Blockchains as state machines

Throughout this yellow paper, we will be discussing Themelio as a transaction-based state machine, a conceptual framework introduced by the creators of Ethereum in their yellow paper. What this means is that a blockchain starts with a genesis state, which is mutated by transactions over time, finally ending at the blockchain at its current state.

Transactions, in this model, are arcs between valid states, and only states that can be reached by repeatedly applying valid transactions to the genesis state are valid states in the blockchain. Formally, we can say that

$$\sigma’ \equiv \Upsilon(\sigma, T)$$

where $\Upsilon$ is the state transition function, $T$ is a transaction, $\sigma$ is the state before the transaction entered the blockchain, and $\sigma’$ is the state afterwards.

A blockchain, however, does not exactly consist of a linear history of transactions — transactions are collated into blocks, each of which can contain a large number of transactions, and possibly auxiliary data. This collation process then forms a coarse-grained journal of transactions. A more accurate formalization, then, uses a block-level state transition function $\Pi$:

$$ \begin{aligned} \sigma_{i+1} & \equiv \Pi(\sigma_i, B) \newline\ B & \equiv (F, (T_0,T_1,\dots)) \newline\ \Pi(\sigma,B) & \equiv \Omega(B, \Upsilon(\Upsilon(\sigma, T_0), T_1)\dots) \end{aligned} $$

where $\Omega$ is the block sealing function that assembles a final state out of the result of applying all the transactions $T_i$ within block $B$, in addition to a sealing event $F$ which includes per-block actions such as collecting fees.

We believe that treating a blockchain as fundamentally a state machine is a much more helpful model than simply a series of transactions, even for coin/UTXO-based blockchains like Themelio. Furthermore, Themelio extensively uses explicit on-chain representations of the current blockchain state, rather than making most of the state implicit as in Bitcoin.

A note on notation

We introduced the notion of seeing the blockchain in terms of state transitions using mathematical notation akin to that used in existing work such as the Ethereum yellow paper. However, standard mathematical notation poses an unnecessary obstacle to clarity in two common situations:

- There isn’t a reasonable way of representing data with many named fields (“structs”). Sets of key-value tuples don’t capture the fact that a canonical field ordering exists, while straight tuples of values force the keys of a struct $s$ to be the extremely inconvenient $s_1$,$s_2$,etc

- When we need to introduce many variables, the mathematical convention of using single-letter variables hinders clarity just like code that uses single-letter variables. It’s often difficult to keep track of a bunch of uppercase, lowercase, and Greek letters that aren’t shorthand for obvious words.

Thus, for the remainder of the paper, we will use a “hybrid” approach:

- Actions will be written in terms of both mathematical functions and pseudocode

- Datatypes will be defined using the Rust programming language

- Names are often “codelike”, i.e. we might name a transaction $\mathsf{foobar}$ rather than $T_1$.

We hope this combines the clarity of “pseudocode notation” and the succinctness of mathematical notation.

State transitions a glance

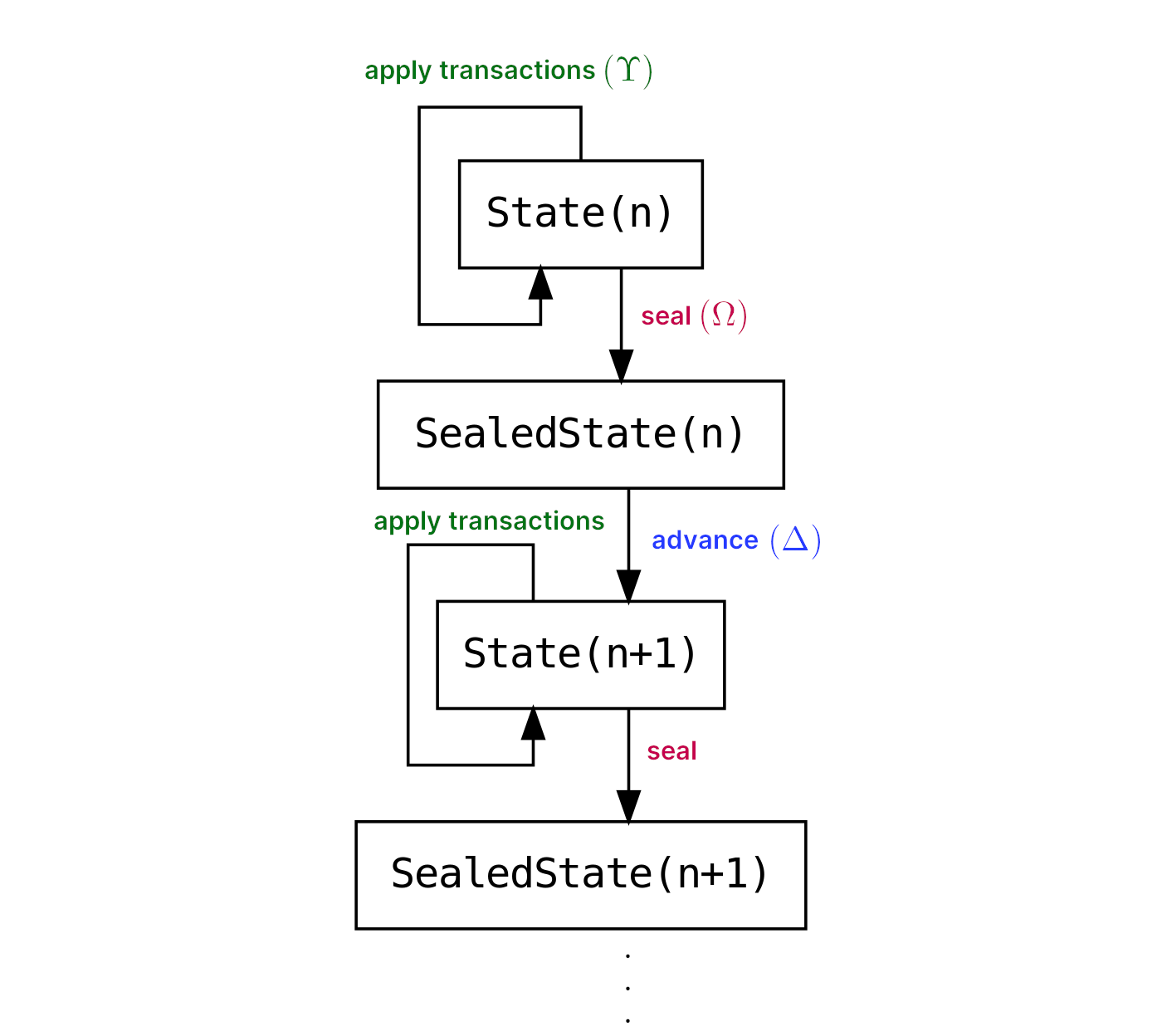

Let’s first take a look at the basic flow of Themelio’s state transitions. As the following picture illustrates, this is based on two basic datatypes State and SealedState. Both of these datatypes will be described in further detail later.

State: transaction-level state

State is the datatype representing the transaction-level state in Themelio. Transactions can be applied to States using the state-transition function $\Upsilon$.

However, transaction-level state transitions cannot create new blocks. With only $\Upsilon$, each State is “stuck” at a particular height; there is no transaction that can force the blockchain to grow to a new height.

Thus, $\Upsilon$ can also be considered the intraheight state transition function, and transactions intraheight state transitions. State can also be thought of as representing the incomplete next block that is being built.

When a block is ready, the State is sealed with the block sealing function $\Omega$ to produce a SealedState.

SealedState: block-level state

SealedState represents the block-level state in Themelio, and corresponds to a certain block height. It is “sealed” in the sense that no more transactions at that block height can be accepted. SealedStates are the subject of blockchain consensus, and the canonical blockchain state is defined only through a series of SealedStates.

The only operation possible on a SealedState is to advance it, converting it to a State that accepts transactions for the next block.

Common functions & datatypes

We now discuss some supporting functions and datatypes that will be recurring in our description of Themelio’s logic:

Serialization

Themelio uses bincode serialization. Bincode has the following properties that make it very suitable for serializing Themelio data:

- Very fast

- Well-integrated with Rust’s

serdeserialization ecosystem - Each serializable object has one canonical serialization. This makes concepts like “the hash of a transaction” trivially well-defined.

In particular, we use bincode with:

- Little-endian, varint encoding of integers

- Trailing bytes banned

(see the source code)

We omit serialization and deserialization from our algorithm descriptions. For example, the hash of the bincode serialization of $v$ is simply denoted $H(v)$.

Cryptography

HashValrepresents a 256-bit hash, generally an output of the BLAKE3-256 hash function. The BLAKE3-256 hash function of a value $v$ is denoted $H(v)$, while the BLAKE3-256 keyed hash with key $k$ is denoted $H_k(v)$.Ed25519PKrepresents an ed25519 public key.Ed25519SKrepresents an ed25519 secret key.

Sparse Merkle trees

Key-value mappings in the Themelio state are generally represented as sparse Merkle trees. Sparse Merkle trees use some neat tricks to efficiently encode a Merkle tree with $2^{256}$ elements, which can be used as a mapping from 256-bit keys to values. An important property is that given any SMT of $N$ elements, there is a 256-bit root hash that uniquely identifies the dictionary, and proofs of inclusion and exclusion of size $\Theta(\log N)$ can be produced. Anybody with the root hash can use these proofs to verify that a certain key-value binding either exists or doesn’t exist in the SMT. The specifics can be seen in the autosmt crate of themelio-core.

On this page, a typed SMT between datatypes K and V, SmtMapping<K, V>, is often used. This denotes a SMT mapping between $H(k), k \in K$ and values of type $V$. Given a value $M$ of type SmtMapping<K,V>, we also write

- $v=M[k]$ to denote the value mapped to by $k$

- $\pi=\mathsf{Pie}(M, k, v)$ to denote a proof of in/exclusion that $k$ is in $M$

SMTs allow us to commit to large datasets succinctly, and is key to thin-client scalability in Themelio.

World state

Overview of elements

The world state, State, is the basic structure that encapsulates all the information needed to validate a single transaction. There is a one-to-one mapping between world states and entire blockchain histories, and other concepts such as the block-level SealedState are derived from State.

State is defined as follows:

pub enum NetID {

Testnet = 0x01,

Mainnet = 0xff,

}

pub struct State {

// Identifies the network.

pub network: NetID

// Core state

pub height: BlockHeight,

pub history: SmtMapping<BlockHeight, Header>,

pub coins: SmtMapping<CoinID, CoinDataHeight>,

pub transactions: SmtMapping<HashVal, Transaction>,

// Fee economy state

pub fee_pool: CoinValue,

pub fee_multiplier: u128,

pub tips: CoinValue,

// Melmint/Melswap state

pub dosc_speed: u128,

pub pools: PoolMapping,

// Consensus state

pub stakes: SmtMapping<HashVal, StakeDoc>,

}

We now take a look at its individual elements.

Core state

Network ID

The state always carries a network ID, which identifies whether the state belongs to the canonical “mainnet” (NetID::Mainnet) or a temporary “testnet”. The genesis state has a hardcoded network ID, and this ID can never be changed by any state transition. This makes different network separate at the level of the state-transition function.

Height and history

The first two elements position the state within the series of blocks that form the blockchain:

State::heightis number of blocks since the beginning of the blockchain. Thus, we talk about the block with height 0, 1, 2, ….BlockHeightis a type alias foru64.State::historyis a SMT that maps each previous height with aHeader.Headeris a fixed-size type that summarizes and commits toState:

pub struct Header {

pub network: NetID,

pub previous: HashVal,

pub height: BlockHeight,

pub history_hash: HashVal,

pub coins_hash: HashVal,

pub transactions_hash: HashVal,

pub fee_pool: CoinValue,

pub fee_multiplier: u128,

pub dosc_speed: u128,

pub pools_hash: HashVal,

pub stake_doc_hash: HashVal,

}

Coin mapping

The most important component of Themelio’s world state is the coin mapping, State::coins. Each key in this SMT is a CoinID, a structure that uniquely identifies a coin by the hash of the transaction that produced it, as well as an index into its outputs:

pub struct CoinID {

pub txhash: HashVal,

pub index: u8,

}

For example, CoinID{txhash: foobar, index: 1} identifies the second output of the past transaction with hash foobar.

Each CoinID maps to a CoinDataHeight:

pub struct CoinData {

pub covhash: HashVal,

pub value: CoinValue, // alias for u128

pub denom: Vec<u8>,

}

pub struct CoinDataHeight {

pub coin_data: CoinData,

pub height: u64,

}

This essentially encapsulates the transaction’s “associated data”. More specifically:

covhashspecifies the hash of the MelVM covenant that constrains the transactions allowed to unlock this coinvaluespecifies the value of the transactiondenomidentifies the denomination of the coin. Generally, this is the hash of the transaction that first created the new denomination. There are three special cases for builtin assets:midentifies micromelssidentifies microsymsdidentifies microergs

The basic action of a transaction is to remove coins from State::coins and put newly created coins in.

Transaction mapping

The transaction mapping contains all the transactions within the last block, mapping the transaction hash $H(T)$ to the transaction $T$. Transactions themselves are structures which we’ll describe in a later section.

Note that the world state does not anywhere contain the ordering of the transactions. This is because transactions within a block are unordered: unlike almost all existing blockchains, there is no defined order of transactions beyond which block they belong to. As we will see in, this allows for easy parallelization of transaction processing.

Fee economy state

The fee economy state consists of:

State::fee_pool, the fee pool of accumulated base fees that funds staker rewards. This can be thought of as belonging to all stakers.State::fee_multiplier, the fee multiplier that scales the amount of fees transactions are required to have.State::tips, the tips that are fees local to this block, paid to the block proposer when thisStateis sealed.

These variables interact with Themelio’s fee system, which we will describe in the transaction-level and block-level state transition functions.

Melmint/Melswap state

The Melmint/Melswap state is used to control the Melmint mechanism that stabilizes the value of each mel. This consists of:

State::dosc_speed, the DOSC speed that measures how much work the fastest processor can do in 24 hours.State::pools, a mapping from token denominations to values of typePoolState

The precise ways these variables are used are discussed in the Melmint/Melswap specification.

Consensus state

The consensus state is used to keep track of the stakers that participate in Themelio’s consensus. For every transaction $T$ that stakes a certain number of syms, it maps $H(T)$ to a value of type StakeDoc:

pub struct StakeDoc {

pub pubkey: Ed25519PK,

pub e_start: u64,

pub e_post_end: u64,

pub syms_staked: CoinValue,

}

The fields of StakeDoc have the following significance:

pubkeydenotes the ed25519 public key of the staker, used in consensuse_startdenotes the first epoch (period of 100,000 blocks) that the staker has voting power. This must be greater than the epoch in which $T$ was confirmed.e_post_enddenotes the first epoch after the last epoch in which the staker has voting power. For example, if an staker has voting power for epochs 1, 2, and 3, thene_post_endis 4.syms_stakeddenotes the number of syms staked by this staker.

The details of how these values are used will be discussed in the state transition functions.

Blocks, transactions, and state transitions

We now look at the actual structure of blocks and transactions in Themelio, which will also let us discuss the core state-transition functions of $\Upsilon$ (apply), $\Omega$ (seal), and $\Delta$ (advance).

Transactions

We start by taking a look at the structure of transactions, as well as the different kinds of transactions:

pub struct Transaction {

pub kind: TxKind,

pub inputs: Vec<CoinID>,

pub outputs: Vec<CoinData>,

pub fee: u64,

pub covenants: Vec<melvm::Covenant>,

pub data: Vec<u8>,

pub sigs: Vec<Vec<u8>>,

}

pub enum TxKind {

Normal = 0x00,

Stake = 0x10,

DoscMint = 0x50,

Swap = 0x51,

LiqDeposit = 0x52,

LiqWithdraw = 0x53,

Faucet = 0xff,

}

Transaction’s fields have the following meanings:

kind: a byte denoting what kind of transaction the transaction is. Most transactions are of typeNormal.inputs: a vector of coins, identified byCoinID, that the transaction is spendingoutputs: a vector of coins, described by theirCoinData, that the transaction is creatingfee: total fees paid, in µmelcovenants: a vector of MelVM covenants, used to “fill in” the covenant hashes in the input coins’ associated datadata: arbitrary associated datasigs: a vector of “signatures”, or malleable associated data. This is used when computing hashes: given a transaction $T$, the hash $H(T)$ is actually $H(T’)$, where $T’$ has an emptysigsfield.

Applying a transaction to the world state

Now that we know the elements of each transaction $T$, we can describe the transaction-level state transition function $\Upsilon$. Applying a transaction to the state involves three steps: $\Upsilon^I$, where the inputs of the transaction are spent, $\Upsilon^O$, where the outputs of the transaction are added to the state, and $\Upsilon^S$, where effects and constraints of non-ordinary kinds are applied.

The algorithm of applying and verifying a transaction against a world state is described as follows. We will discuss ``special’’ transactions, the fee economy, and MelScript constraints separately.

Spending a transaction’s inputs

We check the MelVM covenants of each coin, and make sure the input and output coins are balanced for each denomination. The MelVM covenants are not stored in the coin — only their hashes are — so the transaction must supply the contents of the covenants in the covenants field.

- $\Upsilon^I(\sigma, T)$:

- for each $\mathtt{coinid}$ in $T.\mathtt{inputs}$

- if $\mathtt{coinid.txhash}$ is a key in $\sigma.\mathtt{stakes}$, then the coin is frozen and we abort.

- remove $\mathtt{coinid} \Rightarrow \mathtt{coindataheight}$ from $\sigma.\mathtt{coins}$

- find $\mathtt{cov}$ s.t. $\exists h \in T.\mathtt{covenants}$ where $H(\mathtt{cov}) = h$

- check that $T$ satisfies the MelVM covenant $\mathtt{cov}$

- check that $T$’s inputs and outputs are balanced: for every denomination that is not the empty string, total number created (including fees) must equal total number spent. One exception: for $\mathtt{DoscMint}$ transactions, erg-denominated “balancing” is ignored and deferred to $\Upsilon^S$.

- apply fees:

- check that $T.\mathtt{fees} > \mathsf{Weight}(T)\times\sigma.\mathtt{fee\_multiplier}$

- increment $\sigma.\mathtt{tips}$ by $T.\mathtt{fees} - \mathsf{Weight}(T)\times\sigma.\mathtt{fee\_multiplier}$

- increment $\sigma.\mathtt{fee\_pool}$ by $\mathsf{Weight}(T)\times\sigma.\mathtt{fee\_multiplier}$

- return the changed $\sigma$

- for each $\mathtt{coinid}$ in $T.\mathtt{inputs}$

Applying a transaction’s outputs

No checking is done in this phase; we simply add the outputs into the state. For coins with the denomination of an empty string, we replace the denomination with the hash of the transaction; this is how Themelio implements custom tokens.

- $\Upsilon^O(\sigma, T)$:

- for each $i$th $\mathtt{coindata}$ in $T.\mathtt{outputs}$

- if $\mathtt{coindata.denom}$ has length zero,

- set $\mathtt{coindata.denom}$ to $H(T)$

- insert $\mathtt{CoinID\{txhash: H(T), index: i \}}$ into $\sigma.\mathtt{coins}$

- if $\mathtt{coindata.denom}$ has length zero,

- return the changed $\sigma$

- for each $i$th $\mathtt{coindata}$ in $T.\mathtt{outputs}$

Applying “special” actions

Here we handle all the special actions of non-Normal transactions.

- $\Upsilon^S(\sigma,T)$:

- if $T.\mathtt{kind}=\mathtt{DoscMint}$

- let $\mathtt{cdh}=\sigma.\mathtt{coins}[T.\mathtt{inputs}[0]]$

- if $\sigma.\mathtt{height} - \mathtt{cdh.height} < 100$ then abort (can’t measure such small timeframes accurately)

- let $\chi=H_{\sigma.\mathtt{history}[\mathtt{cdh.height}]}(T.\mathtt{inputs}[0])$

- let $(d, \pi) = T.\mathtt{data}$

- verify MelPoW proof with seed $\chi$, difficulty exponent $d$, and proof $\pi$ (TODO)

- measure speed of minter $\mathtt{my\_speed}$ as $2^d/(\sigma.\mathtt{height} - \mathtt{cdh.height})$

- let $\delta=\frac{2^d \times \mathtt{my\_speed}}{\sigma.\mathtt{dosc\_speed}}$

- ensure that the total output DOSC do not exceed $\delta$

- else if $T.\mathtt{kind}=\mathtt{Stake}$

- check that $T.\mathtt{data}$ deserializes to a valid

StakeDoc - check that the first input of $T$ is $s$ Sym, where $s$ is the value in

StakeDocs - check that

e_post_endis greater thane_startin theStakeDoc, and thate_startis in the future - insert $H(T) \Rightarrow T.\mathtt{data}$ into $\sigma.\mathtt{stakes}$.

- check that $T.\mathtt{data}$ deserializes to a valid

- if $T.\mathtt{kind}=\mathtt{DoscMint}$

Batch-applying transactions

We note two peculiar properties of Themelio transactions. First, for normal transactions where $\Upsilon^S$ is a no-op, it’s clear that for any set of transactions $T_1,T_n$, we obtain the same final state no matter in what order we apply the transactions to a starting state. There may be orders in which the application fails halfway through (for example, attempting to apply $T_j$ before $T_i$ while $T_j$ spends an output of $T_j$), but for all valid orders, the result will be the same. Intuitively, this is because all transactions do is remove and add coins into the state.

Furthermore, the “special action” function $\Upsilon^S$ is carefully designed so that this same property, which we call

order-independence, holds for all transactions. An interesting

implication of order-independence is that there is no such thing as the

order of transactions within a block — blocks contain sets, not

lists, of transactions. This is why for a State $\sigma$, $\sigma.\mathtt{transactions}$ is an unordered mapping, not a list, of transactions.

Secondly, for each transaction the order in which $\Upsilon_I$ and $\Upsilon_O$ is applied does not actually matter. That is, the transaction can actually add its outputs to the state before spending its inputs, and this will always behave exactly the same way as the “natural” order. This is because a transaction can never either directly or indirectly refer back to its own outputs in its inputs, due to preimage resistance of the hash function.

These two properties allow us to batch-apply an unordered set of transactions that may depend on each other — given a set of transactions $T^{+}={T_i}$ and a starting state $\sigma$, produce $\sigma’ = \Upsilon^+(\sigma, T^+) = \Upsilon(\dots\Upsilon(\Upsilon(\sigma, T_1), T_2), \dots T_n)$ where $(T_1,\dots,T_n)$ is some topological sorting of the transactions — without actually computing a topological sort at all. This is done by first apply all the outputs, and then applying the inputs and special functions:

- $\Upsilon^+(\sigma, T^+)$:

- for $T_i \in T^+$

- set $\sigma= \Upsilon^O(T_i)$

- for $T_i \in T^+$

- set $\sigma= \Upsilon^I(T_i)$

- for $T_i \in T^+ | T_i.\mathtt{kind} \neq \mathtt{Normal}$

- set $\sigma= \Upsilon^S(T_i)$

- return $\sigma$

- for $T_i \in T^+$

Blocks

We now talk about blocks, and $\Omega$, the “state-sealing” function that builds blocks.

State sealing

SealedState, representing a canonical state at a certain block height, simply wraps a State and an optional ProposerAction:

pub struct SealedState {

pub state: State,

pub action: Option<ProposerAction>

}

pub struct ProposerAction {

pub fee_multiplier_delta: i8,

pub reward_covhash: HashVal,

}

SealedState is produced by the state-sealing function $\Omega(\sigma, P)$. The “proposer action” $P$ is an optional non-transaction action that the block proposer uses to pay himself the fees incurred in the block, as well as up/downvoting the fee level. More specifically,

fee_multiplier_deltarepresents how much to change $\sigma.\mathtt{fee\_multiplier}$, where -128 represents the biggest possible decrease and 127 representins the biggest possible increase. The maximum amount the fee multiplier can change is $1/128$ of the fee multiplier.- Note: TIP-901 is the canonical algorithm for applying changes to fee multipliers. In particular, handling rounding when the fee multiplier is very small is rather tricky.

reward_destis the covenant hash that the fees of the block will be sent. This is generally an address that the block proposer controls. Every block height, the proposer withdraws $2^{-16}$ times the fee pool, as well as all the tips. This is implemented by adding a coin “out of nowhere” into $\sigma.\mathtt{coins}$.

The state-sealing function is thus:

- $\Sigma=\Omega(\sigma, P)$:

- apply all Melmint/Melswap-related sealing functionality, described in its specification

- let $\mathtt{max\_movement}=\sigma.\mathtt{fee\_multiplier}/128$

- let $\mathtt{scaled\_movement}=\mathtt{max\_movement}\times P.\mathtt{fee\_multiplier\_delta}/128$

- increment/decrement $\sigma.\mathtt{fee\_multiplier}$ by $\mathtt{scaled\_movement}$

- let $\mathtt{base\_fees}=\sigma.\mathtt{fee\_pool}/2^{16}$

- let $\mathtt{total\_reward}=\mathtt{base\_fees}+\sigma.\mathtt{tips}$

- set $\sigma.\mathtt{tips}=0$

- let $\mathtt{pseudocoin\_id}=\mathsf{RewardPseudo}(\sigma.\mathtt{height})$

- let $\mathtt{pseudocoin\_data}$ be a

CoinDataHeightwith aCoinDatathat transferstotal_rewardµmel to $P.\mathtt{reward\_covhash}$ - insert $\mathtt{pseudocoin\_id} \Rightarrow \mathtt{pseudocoin\_data}$ into $\sigma.\mathtt{coins}$

- return

SealedStatewith $\sigma$ and $P$

State advancement

Given a confirmed SealedState at height $n$, how does the blockchain proceed? It needs to somehow “advance” the SealedState to a State at height $n+1$. This is the purpose of the state-advance function, $\sigma^0_{n+1}=\Delta(\Sigma_n)$:

- Insert the current block header into

State::history - Advance height by 1

- Remove all stale entries in

State::stakes - Update

State::dosc_speed

“Block” representation

We can now present Block: all the information required to get from a SealedState at height $n$ to a SealedState at height $n+1$:

pub struct Block {

pub header: Header,

pub transactions: im::HashSet<Transaction>,

pub proposer_action: Option<ProposerAction>,

}

Note that this implies Block is entirely a derived concept for ease of serialization. In this sense, Themelio can be thought of as not really a “blockchain” at all!