In this page, we specify Synkletos, Themelio’s consensus algorithm. We give a concrete instantiation of the concepts discussed in the Synkletos whitepaper.

Basic concepts

Let’s start by introducing some basic concepts that are needed to understand Synkletos.

Three consensus roles

In Themelio, all participants in the blockchain belong to one of three roles:

- Stakers directly participate in consensus. They have stake, denominated in Sym, locked up on-chain, and receive consensus voting power in exchange. Votes from stakers owning at least 2/3 of the on-chain stake — a quorum — is needed to confirm a block.

- Auditors correspond to “full nodes” in other blockchain. They do not own stake, but replicate and validate the output of the staker consensus. They not only provide a “CDN” for the blockchain, but more importantly by using a nuking procedure, they shut the network down if a quorum of stakers produces invalid results.

- Clients are pure consumers of consensus. They do not replicate the blockchain, but trust consensus proofs provided by the stakers that commit to a particular blockchain state, and as long as the stakers are trustworthy and the auditors are operating correctly, clients cannot be fooled.

In this document, we largely focus on the stakers, since they are the one who directly participate in consensus.

Proof of stake

Stakers lock up Sym, a token that is used only for proof-of-stake. On chain, this is represented by coins of denomination Denom::Sym, and similar to the mel, 1,000,000 on-chain units (µsym) equals “one sym”.

Compared to most other PoS mechanisms, Themelio’s PoS has two uncommon features:

- Stakers precommit to how long to lock up their syms. There is no mechanism for early withdrawal.

- The period of time in which a staker has voting power is not perfectly aligned with the time in which the syms are locked up. Instead, voting power always stays constant within an epoch of 200,000 blocks (~ 69 days 10 hours).

Both of these features are designed to mitigate the “weak subjectivity” problem and maximize security and usability for clients. We will discuss the detailed mechanics in a subsequent section.

Stakes, epochs, and slashing

In this section, we discuss the on-chain mechanics of keeping track of stakers’ stakes and their associated consensus votes. This is separate from the actual consensus algorithm, which takes in these stakes as an input and decides on blocks.

Stakes

We start by looking at how stakers lock up syms. To stake a sum of sym, a transaction $T$ with kind Stake is sent, the first output of which must be denominated in µsym, and the data field of which is the following structure:

pub struct StakeDoc {

/// Public key for signing consensus.

pub pubkey: Ed25519PK,

/// First 100,000-block epoch when staker has power.

pub e_start: u64,

/// Ending epoch. This is the epoch *after* the last epoch in which the syms are effective, and the last epoch in which the syms are locked.

pub e_post_end: u64,

/// Number of µsyms staked.

pub syms_staked: u128,

}

The blockchain then checks that:

e_startis greater thancurrent_block_height/STAKE_EPOCH. That is, the starting epoch must be in the future.e_post_endis greater thane_start.syms_stakedis exactly equal to the value of the first output of the transaction

If all these conditions hold, then the first output of the transaction is locked until the end of epoch e_post_end. This is accomplished by adding a binding $H(T) \Rightarrow T.\mathtt{data}$ into the stakes binding in the state, which prevents the first output of $T$ from ever being spent until the entry is removed.

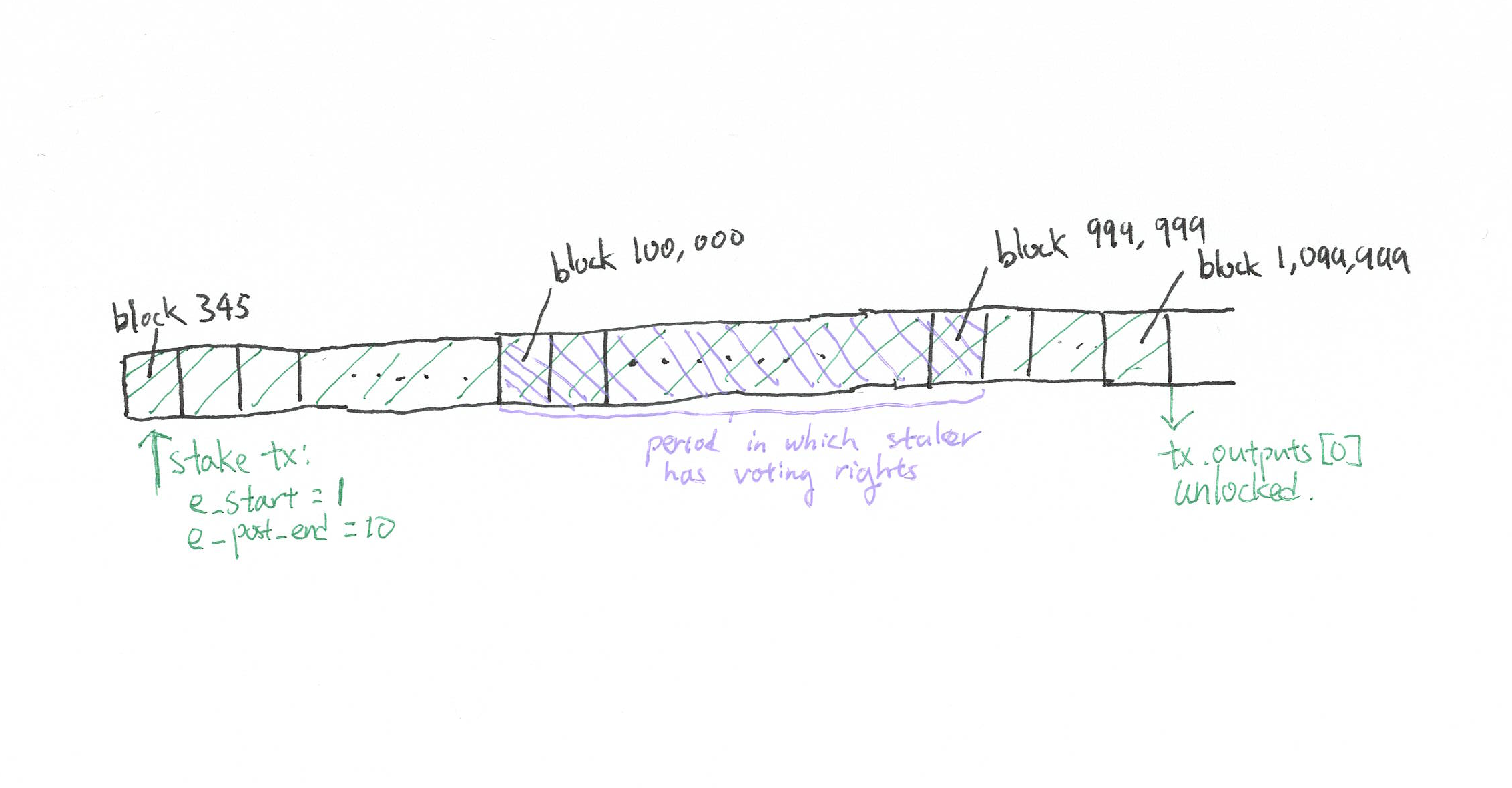

Here is an illustration of a stake that is committed into the blockchain in block 345, with e_start=1 and e_post_end=10. Note that the staker gains voting rights starting at the beginning of epoch 1 and loses them right before epoch 10.

Through the consensus algorithm (detailed later), a consensus proof is produced for every block, containing signatures corresponding to the owners of at least 2/3 of the staked syms whose StakeDocs confer voting rights for that block’s height.

Epochs and voting rights

A consequence of having voting rights start and end on epoch boundaries is that within a single epoch, the set of voting stakers is static. That means that we only need a copy of the State::stakes mapping from the end of the previous epoch to validate all consensus proofs in the present epoch.

Thus, the first step any client or auditor must take to validate consensus results is to obtain, in a secure manner, this stake mapping. Yet to validate this stake mapping, the voting power distribution of the previous epoch must be sought, which requires obtaining and validating an even earlier stake mapping! This procedure terminates when the client hits a stake mapping that it already knows.

Slashing and nuking

On evidence of misbehavior, stakers can be slashed. This is done by broadcasting a transaction with kind Slash, with data containing:

pub struct SlashEvidence {

bad_staker: Ed25519PK,

header_a: Header,

header_b: Header,

sig_a: Vec<u8>,

sig_b: Vec<u8>

}

This slash evidence contains two headers at the same height with signatures from the same staker — incontrovertible evidence that the staker attempted equivocation.

TODO: We need other kinds of slashing too. But the sort of slash proofs required is not always clear, and we hope to use the betanet period to get community feedback on what misbehavior should be slashed.

Furthermore, if invalid blocks are ever confirmed by a quorum, auditors nuke the network by refusing continued operation and rebroadcasting evidence of the invalid blocks to the entire auditor network. This makes breaking safety without quickly shutting down the network extremely difficult even with the cooperation of all consensus participants, making the set of adversaries who would benefit from breaking consensus safety much smaller.

Incentives

Proposer selection

Each block in the blockchain isn’t just decided by the whole staker quorum — it also has a proposer whose primary responsibility it is to put together the block. Proposers, strictly speaking, are not part of the blockchain state-transition function, but part of the consensus algorithm, but we discuss them here because they are crucial to the incentive structure of Themelio.

Proposers are allocated pseudorandomly between the stakers, based on their respective weights. This is done at the beginning of each epoch — by the time the epoch starts, who the proposer of each block is is already set in stone:

-

First the entropy seed $\Sigma$ is calculated by a bitwise majority of all the header hashes $h_1,\dots,h_n$ of the previous epoch. That is, the $i$th bit of $\Sigma$ is: $$\Sigma[i] = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } \sum_i h_i>n/2 \ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

-

Then, the proposer of the $n$th block (counting from genesis) is determined by the selection function $\mathsf{Select}(n)$:

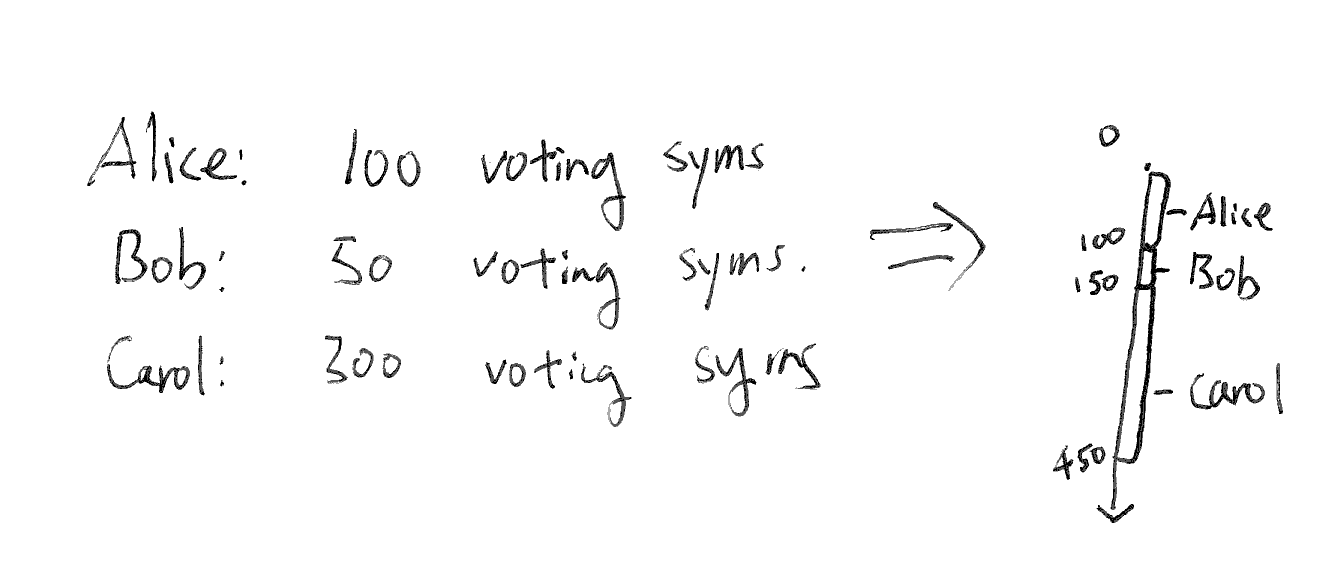

- Lay out all the stakers in lexicographic order of their public keys. Each staker is then assigned a range in the number line, next to the previous one, the size of which is the number of µsym staked, which includes its starting point but not its endpoint:

- Compute a subseed through a keyed hash: $\Sigma_n=H_n(\Sigma) \bmod F$, where $F$ is the smallest power of 2 greater than or equal to the total µsym staked and voting.

- Until returns:

- If $\Sigma_n$ falls into a range that belongs to a staker, that staker is the $n$th proposer

- Otherwise, set $\Sigma_n \gets H(\Sigma_n)$

- Lay out all the stakers in lexicographic order of their public keys. Each staker is then assigned a range in the number line, next to the previous one, the size of which is the number of µsym staked, which includes its starting point but not its endpoint:

The use of an entropy seed calculated by bitwise majority, rather than, say, the block hash of the last block of the previous epoch, resists “stake grinding” attacks, where a malicious proposer at the end of the last epoch brute-forces blocks to ensure that it’s picked disproportionately often in the next epoch. This is based on the “majority beacon” idea by TODO

The selection function essentially gives each proposer slot to stakers with probability proportional to the fraction of staked, voting syms that it owns.

Fees and block rewards

Each block, proposers have the option of collecting fees by using the optional argument in $\Omega$, the block-sealing function (see the yellow paper). These fees have to components: a base fee that is added to a common fee pool, and tips that are given directly to the proposer. The proposer can also withdraw $2^{-16}$ times the fee pool, as well as change the base fee rate up to $1/128$ in one direction.

The upshot is that tips are given directly to the proposer, while base fees, which are charged a rate determined by a sequential, collective vote, are distributed to all proposers, with a slight bias towards proposers in the near future.

A concrete consensus

We now describe Symphonia, the concrete consensus algorithm that, given the set of voting stakers, produces a series of blocks with correct consensus proofs.

Symphonia exposes a simple public interface: every 30 seconds or so, a new confirmed block, consisting of a block $B_i$ and a consensus proof $\Pi_i$ is produced. $\Pi_i$ is simply a set of signatures whose collective vote weight is greater than 2/3 of all the voting power in the current epoch.

Confirmed blocks produced by the mechanism are always consecutive: there will be a separate consensus proof for every block height. This means that the “rest of the network”, regardless of the actual implementation, can pretend like Symphonia is a series of PBFT-style one-shot consensus algorithm instances, each producing a consensus proof.

Internally, however, Symphonia uses a variation of STREAMLET, a “pipelined” algorithm that produces and finalizes blocks separately.

Basic concepts

The blockchain is divided into stake epochs, each lasting 100,000 blocks. Within each stake epoch, the set of voting stakers does not chane. Each voting staker has a vote weight, which is an integer that represents the number of syms staked that is valid for the current epoch.

There is a designated proposer at each height, pseudorandomly assigned to a staker weighted by its voting weight. The proposer of each height within an epoch is predetermined at the beginning of the epoch according to a pseudorandom function, as described in the “proposer selection” section ablve. Thus, it makes sense to talk about the proposer of a block at a height outside an epoch, with respect to the voting set of that epoch.

Each block height is associated with a block time, a predetermined “wall clock” time that the block is supposed to be proposed.

Core algorithm

Symphonia is essentially identical to Streamlet, with two major differences:

-

Blocks must be consecutive

-

All finalized blocks carry consensus proofs that can be verified by third parties who did not observe the consensus protocol.

There are three parts to Symphonia:

-

Propose-Vote: At the block time for block $h$:

-

The proposer proposes $B_h$ extending from the longest[^1] notarized chain it has seen. If there are multiple longest chains, “the longest chain” is the one with the smallest block header hash. If the longest notarized chain terminates at $B_j$ where $j < h - 1$, the proposer also proposes empty blocks at heights $B_{j+1},\dots,B_{h-1}$ within the proposal. These empty blocks must have no transactions and no proposer action present.

-

Every staker votes for the first valid proposal they see from the proposer that extends from the longest notarized chain. This is a signature on $H_\mathsf{vote}(B_h)$.

-

When a block gains votes from stakers owning at least 70% of the stake (a quorum), it becomes notarized. A chain is notarized if all its constituent blocks are notarized.

-

-

Finalize: If in any notarized chain, there are three consecutive non-empty blocks, then the prefix of the chain up to the second of the three blocks is final.

-

Confirm: All honest stakers will sign $H_\mathsf{final}(B_h)$ if $B_h$ is finalized, and will talk to other stakers to assemble a consensus proof $\Pi_h$ consisting of more than 70% signatures on $H_\mathsf{final}(B_h)$. $(B_h, \Pi_h)$ is a confirmed block and will be broadcasted onto the auditor network.

Handling epoch transitions

One special case we need to handle is the transition between stake epochs. At the end of an epoch, we don’t know what set of stakers to use for the next epoch until the last block of the epoch is confirmed. Yet according to the algorithm above, we can’t confirm the last block of the epoch until the next block is notarized. This breaks liveness at the end of epochs.

Thus, we modify the algorithm slightly. At the end of an epoch, stakers continue running the consensus algorithm, except that all “out of bounds” blocks must be empty blocks, and out-of-bounds blocks will never be confirmed, only finalized. This lets the last block of the epoch eventually become confirmed.

As soon as the epoch-ending block is confirmed, stakers start a Symphonia instance for the next epoch (if they still have voting power) but continue broadcasting the epoch-ending confirmed block to the auditor network on demand.

Technical specs

The Melnet instance

All stakers join the Melnet network identified as testnet-staker, as

well as the auditor network (testnet-auditor). Melnet maintains a

connected graph of all stakers, allowing reasonably efficient gossip.

This is exposed to each staker as a list of neighbors which the staker

can directly send messages to.

The entire protocol uses the single Melnet verb symphonia that returns

Option<ConfirmResp>. To broadcast a message, we mean to send it to

up to 16 randomly selected neighbors.

Message format

All messages are sequenced and signed. More specifically, the format of an on-wire message is as follows:

/// Message sent *to* a node

pub struct SignedMessage {

pub sender: Ed25519PK,

pub signature: Bytes, // over (sequence, body)

pub sequence: u64, // monotonically increasing. clock+ctr

pub body: Message,

}

pub enum Message {

Proposal(ProposalMsg),

Vote(VoteMsg),

GetConfirm(GetConfirmMsg)

}

pub struct ProposalMsg {

pub proposal: AbbreviatedBlock,

pub last_nonempty: Option<(u64, HashVal)>,

}

pub struct VoteMsg {

pub voting_for: HashVal,

}

/// Message that responds to a GetConfirmMsg

pub struct ConfirmResp {

signatures: BTreeMap<Ed25519PK, Bytes>

}

All messages with invalid signatures are immediately discarded without further processing. For valid messages, each node keeps track of the last sequence number from a given sender; only messages with higher sequence numbers are accepted. This prevents the same broadcasted message from looping in the network indefinitely. When messages are rebroadcast, nothing is changed.

Proposing a new block

At each block time, the designated proposer sends a ProposalMsg with

Proposal containing its proposed block. If the LNC needs to be

extended by possibly many empty blocks to reach this height, the

last_nonempty field is set to the height and hash of last non-empty

ancestor of the proposed block.

Voting for the proposal

On receiving a proposal, a staker will first see if it’s signed by the correct proposer for the given height and properly extends the LNC. If not, it will immediately discard the proposal.

Otherwise, it will wait until it has seen all its constituent

transactions and is able to construct a proper (series of) Block(s).

It will then validate the block. If it passes validation, a VoteMsg

will be broadcast.

Finalizing and confirming blocks

Finalized blocks are confirmed by repeatedly asking a random neighbor

for confirm responses with GetConfirmMsg. Each staker will respond

with a mapping containing its own confirmation signature, as well as all

the ones it has gotten from its neighbors.

This will rapidly construct enough signatures to form a quorum, at which point the confirmed block can be broadcast onto the auditor network.